Cardiff Theosophical Society

206 Newport Road,

Cardiff, Wales, UK, CF24 -1DL

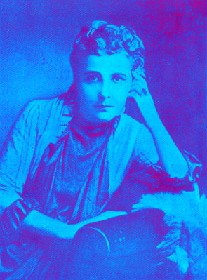

Annie

Besant

England and India

by

Annie Besant

First Published 1906

Return to Annie Besant

Selection

Return to

History of the Theosophical Society

Cardiff Lodge Homepage

THE relations

between conquering nations and subject peoples form a question of the present

day which may well tax the thought of the most thoughtful, as well as stir the

feelings of the most sensitive. How these relations should be carried on, how

both conquering nation and subject people may profit by the links that arise

between them - on the answer to that problem depends much of the future

progress of the world, and I have thought that, with the traditions that are

associated with the name of South Place, I might well take up before you this

morning the relations which exist between one of the greatest of conquering

nations and the greatest of subject peoples, and see how far it is possible to

lay down certain lines of thought, which may possibly be of help to you in your

own thinking, which may possibly suggest to you ideas which, perchance,

otherwise might not have come in your way.

Now, every

two nations that come into touch the one with the other should, it is very

clear, each have something to learn, each have something to teach, and this is

perhaps pre-eminently the case where two such nations as India and England are

concerned. Where England has to do with savage peoples her path is

comparatively simple; where she has to do with a nation far older than her own civilisation, a nation with fixed and most ancient

traditions, a nation that was enjoying a high state of civilisation

long ere the seed of Western civilisation was sown -

where she has to do with such a people, the relations must needs be complicated

and difficult, difficult for both sides to understand, difficult for both sides

to make fruitful of good rather than of evil. And I know of no greater service

that can be rendered either in this land or in that, than the service of those

who try to understand the question and to draw the nations closer together by

wisdom instead of driving them further apart by ignorance and by prejudice.

Now it seems

to me that with regard to India, the subject may fall quite naturally under

three heads: first, the head of religion; then, of education; and then, of

political relations, under which latter I include the social conditions of the

people. Let me try, then, under these three headings to suggest to you certain

ideas as to English relations with India, which may possibly hereafter bear fruit in your

minds, if they be worthy to do so.

I said that,

when two nations come together, each has something to teach and something to

learn, and that is true. So far as religion is concerned, I think India has more to teach than she has to learn. So far

as education is concerned, much has to be done on both sides, but on the whole,

in most respects, England has more to teach there than to learn. With regard to

political conditions, there both nations have much to learn in mutual

understanding and in adaptation to this old civilisation

of India of methods of thought, of rule, of social conditions utterly alien

from her own conditions, so that changes, if it be wise to introduce them, must

be brought about with the greatest care, the greatest delicacy, after the

longest and most careful consideration.

1) Let us

take, then, first, the question of religion, on which I submit to you that

India has more to teach than she has to learn; and I say that for this reason,

that almost everything which can be learned from Christianity exists also in

the eastern faiths, and you have with regard to this to remember in India that

you are dealing with a people of various faiths and many schools of thought,

some of them exceedingly ancient, deeply philosophic, as well as highly

spiritual. Now, seventy per cent of the population of India are Hindûs, belong to

one great religion, which includes under that name an immense variety of

philosophic schools and sects. For when we speak of Hindûism,

we are not speaking of what you might call a simple religion, such as is modern

Christianity, though even there you have divisions enough, but of a religion

which has always encouraged to the fullest extent the freedom of the intellect,

and which recognizes nothing as heresy which the intellect of man can grasp,

which the thought of man can formulate. You have under that general name the

greatest diversity of thought, and always Hindûism

has encouraged that diversity, has not endeavoured to

check it. Hindûism is very, very strict in its social

polity; it is marvellously wide in its theological,

its ethical, its philosophical thought. It includes even on one side the Chãrvaka system, the most complete atheism, as it would

here be called; while it includes on the other, forms of the most popular

religious thinking that it is possible to conceive. The intellect, then, has

ever been free under the scepter of the religion which embraces seventy per

cent of the great Indian population.

The majority

of the remaining thirty per cent are followers of the great Prophet of Arabia, Muhammad, and amongst them today there are

great signs of awakening of thought, there are great signs of revival of deeper

philosophical belief. While the majority of them still are, I was almost going

to say, plunged in religious bigotry, from western and from eastern

standpoints, rather repeating a creed than understanding a philosophy, there is

none the less at the present day a very considerable awakening, and a hope that

the great faith of Islãm may stand higher in the eyes

of the world by knowledge and by power than it has done for many a hundred

years in the past. Then, in addition to this - the Hindû

with its seventy per cent, the faith of Islãm, which

counts some fifty millions of the population - you have Christianity, imported,

of course, from the West, not touching the higher classes of the Hindûs at all, but having a considerable following,

especially in the South, among the most ignorant, among the most superstitious

people; you have the Pãrsi community, a thoughtful,

learned and wealthy community, though a very small one, only numbering, I

think, some 80,000 people; you have the Jain community, also very wealthy, and

having among it a certain number of very learned men, a community whose rites

go back to the very early days of Hindû thought and Hindû civilisation; and you have

in addition to this the warrior nation of the Sikhs, bound together by their

devotion to their great Prophet, and forming today a most important part of the

fighting strength of the English Empire in India. Buddhism has scarcely any

power in India proper. It rules in Burma, and it rules in Ceylon, both, of course, forming part of the Indian

Empire, but in India proper it is practically non-existent.

In this way, then,

you have a country, including Burma and Ceylon, in which you have clearly

marked out some seven different faiths, and you have a ruling nation, Christian

in its theory, and entirely unsectarian so far as its

rule over the people is concerned; but inevitably under the shadow of that

conquering nation there grows up an immense missionary propaganda in India,

which is strong, not by its learning, not by the spirituality of its

missionaries, but simply from the fact that they belong to the conquering, to the

ruling, people, and so have behind them, in the mind of the great mass of the

Indians, the weight which comes by the authority of the English Empire, as you

may say, backing that particular form of faith. Now it is this condition that

you want to understand, if you would deal fairly with the religions question in

India. The most utter impartiality is the rule of the

Government, but it is that simple impartiality which may be said to take up the

position that all religions are equally indifferent. This is not the kind of

spirit that is wanted in a country where religion is the strongest force in

life. You need a sympathetic impartiality, not an impartiality of indifference;

and it is that in which so far the government has naturally very largely

failed. You want in India at the present time a definite recognition of the

fact that the religions that are there, and that rule the hearts of the great

mass of the people and the minds of the most thoughtful and learned of the

nation - that these religions are worthy of the highest respect, and not of

mere toleration. You have to realise that the

missionary efforts there do an infinity of harm and very little good; that they

set religion against religion and faith against faith; whereas what you want in

India is the brotherhood of religions, and the respect of men of every faith

for the faiths which are not theirs. You need there the teaching and the spirit

of Theosophy, which sees every religion as the partial expression of one great

truth. The more aggressive one faith shows itself to be, the more it is

stirring up religious antagonisms and religious hatreds. Danger to the Empire

lies in the aggressive policy of Christianity, whereby large numbers of men,

ignorant of the religions that they attack, treat them with contempt, with

scorn, with insult - that is one of the dangers that you have to consider in

India, when you remember that in the minds of the people England stands behind

the missionary. The Christian missionary converts very, very rarely, in the

most exceptional of cases, any man who is educated, any man who is trained in

his own faith, any man of what are called the higher and thoughtful castes. He

makes his converts among the great mass of the most ignorant of the population;

he makes them chiefly in times of famine and of distress; he makes them more

largely for social reasons than for reasons which are religious in their

nature. By the folly of the Hindûs themselves vast

masses of the Indians have been left without religious teachings altogether,

have been regarded with contempt, have been looked upon with arrogance. It is

among these classes that the Christian missionaries find their converts. Once

such a man is converted to Christianity, he, who before was not allowed to

cross the threshold of a Hindû, is admissible as a

Christian into the house, because Christianity is the religion of the

conquering nation; and you can very well recognize how strong a converting

power that has on the ignorant, on the degraded, on the socially oppressed. It

is not necessary for me to say much on that here, since here nothing much can

be done in this matter. It is rather in India, that one tries to meet that

question, pointing out to the educated and the religious how great a danger to

their own faith, as well as how great a wrong to humanity, it is to neglect

vast portions of the population, and so to drive them, as it were, to find

refuge in an alien creed, which at least treats them with decency, if it cannot

do much for them in ethical training.

This

religious question in India is one that you need to understand, for eastern

teaching is everywhere more and more spreading in the West. I could not help

being amused the other day by a remark of a disconsolate missionary coming back

to America, and declaring that while he was striving to convert people from Hindûism, he found on his return that large numbers of the

educated were tainted with the philosophy that in India he was trying to

destroy. That is perfectly true. Hindû thought is

making its way here in general very much more rapidly than Christianity is

making its way in India; and it is touching the flower of the population here,

whereas Christianity is only touching the poorest and most ignorant in India.

That is why I

said that India had much more to teach than to learn in matters

of religion; she has plenty in her own faith which can train and cultivate the

masses of her people, but that must be done by Hindû

missionaries and not by Christian missionaries. It would be the wisdom of

England to look upon all these religions as methods of training, of guiding, of

helping the people, and to recognize that the work of the Christian in India is

among his own population, is among his own countrymen, is among the Christian

communities, and that he should look on his faith as a sister faith among many,

and not as unique, to which people of other religions are to be converted. The

greatest, perhaps the only serious, danger to English rule in India lies in the

religious question, in the bad feelings stirred up by the missionaries, in the

difficulties that are caused by their lack of understanding of the people.

Theosophy has done much to counteract this danger, and has been striving in

India to stimulate the peoples of the various faiths to take up these religious

questions for themselves, and by their energy in the teaching of their own

religion to cause the spread of religious knowledge which may make each faith

strong within its own borders,

2) Pass from

the religious question to the educational, and here a great danger lies

immediately in front, a danger which arises largely out of that want of

sympathy and that want of understanding which is the chief fault of the English

people as a conquering nation, as a ruler in their relations with subject

peoples. They try to be just, they try to do their duty, they are industrious,

they are hard-working, endeavouring to do the work

which is put into their hands. Their weak point lies in the fact that they are

very unsympathetic, that they cannot put themselves into the place of others,

and that they have a tendency to think they are so immensely superior to others

that whatever is good for them is good for everybody else; they fail to

understand the traditions and the customs which must exist in an ancient

people, a people of high and complicated civilisation,

and this lack of sympathy has a very great bearing on the question of

education. Practically, Indian education, on the higher line, was started by

the wisdom of Lord Macaulay. He began the work of Indian education, and he

began it wisely and well. It has been carried on year after year by a long

succession of Viceroys, who for the most part have done well with regard to the

educational question; but while they have done well, it is perfectly true that

there are great and serious faults in the Indian system, faults which need to

be corrected and which neutralise much of the value

of the education that is given. I have not time to go very fully into these

faults; it must suffice to say that memory has been cultivated to the exclusion

of the reasoning faculty, and that even when science has been taught, it has

been taught by the text-book, and not in the laboratory, it has been taught by

memory, and not by experiment. In addition to that there has been a crushing

number of examinations, forcing the whole life of the boy as well as of the

man, and keeping up a continual strain which has exhausted the pupil ere he has

left the University. It has been forgotten that the Indian student is naturally

studious and not playful enough, that his inclination is to work a great deal

too hard, that what was wanted was the stimulation to play more than the

stimulation to study, that the physical training of the boys was more necessary

to be seen to than the intellectual training. The physical training was left

out of sight, and though carefully looked after in ancient India it was now neglected. As these differences were

overlooked, everything was done to force the intellectual side in an unwise

way, by cramming rather than by organic development of study, and as the

University degrees were made the only passport to Government employment and to

the professions at large, it became a wild desire on the part of the Indian

parent to force his boys on as rapidly as possible, with little regard to the

kind of education that was given. These faults have been seen by the present

Viceroy, and, eager to mend the faults, he sent out a University Commission,

which has just made its report. Now the first fault of that Commission was that

it had only two representatives of India on it, and the rest Englishmen, and

the English members of that Commission were not all acquainted with the nature

of the problems of Indian education. They have issued their Report. The Indian

judge, who was the Hindû member of that Commission,

has issued a minority report, against many of the recommendations made by the

majority, consisting of the English members and one Musulmãn.

The very fact that you get a report divided in that racial way ought at once to

make our rulers pause, and when you find that many of the recommendations of

the majority-report are disapproved by the representative of seventy percent of

the population that you are going to teach, it seems as though it might be wise

if the Government here would look into the matter a little carefully before it

gives its decision. For it is the view of the Indian people, now being

expressed in every way possible, that the report of the Commission strikes a

heavy blow at Indian education, that much of the great work of the past will be

destroyed, and that the education of the future will be placed beyond the reach

of large numbers of the people who hereditarily claim it.

To begin

with, the education is now made more costly, and by that one word you have its

condemnation for India, The fees are everywhere to be raised, so that

University education will be practically beyond the reach of those who need it

most. It is said that many go to the University who are not fit for it; but the

remedy for that is to improve the teaching in your Universities and not to

increase the cost of the education; for by high fees you will not exclude the

idle and the unworthy rich, but you will exclude great masses of the worthy and

industrious poor; and when you remember that it is the Indian tradition that

learning and poverty go together, that the man who is learned has no need of

wealth, that you find the highest caste the poorest caste, although the most

learned - if you could realize that and put yourself in their place, you would

understand the agitation which at present is convulsing the most thoughtful

people in India, when they see that the Government is going to exclude their

sons, the flower of the intellectual population, from all share in education by

the high fees which it is going to impose. It is said by the Commission, that

scholarships may serve for the poorer classes, but you cannot give scholarships

to thousands of that vast population. You can give scholarships to a boy here

and there, but you cannot give them to the great mass; the greatest danger is

the discontent of the thoughtful, and that is the discontent which is being

stirred up at the present time. The truth is, that Lord Curzon,

able as he is, has only five years in which to rule, and he is eager to mark

his Viceroyalty by some great scheme of change. But if England be not careful,

it will be marked by the saddest monument that ever Viceroy has left behind

him, the destruction of the education of a great people, and the shutting out

of vast masses of the intellectual from education whereby they might rise to be

your helpers in the ruling of their country, but shut out from which they

become an element of danger. That is not a thing which it is well to have said

by a subject nation of the type of the Indian nation. It is said among the

thoughtful people now that this is intended to destroy education, in order that

Indians may not have their fair share in the government of their own land. That

is the thought which is spreading, that is the motive which they believe lies

behind the policy of Lord Curzon. They think he

desires to stop education, in order that the Indians may not rise to the higher

posts in their own country, and that is a most dangerous idea to spread through

the most intellectual, through the most thoughtful classes. I have had letter

after letter pleading with me to do something here to prevent this Report from

receiving the sanction of the Government; but how difficult is it to do that

where the people who give the decision are ignorant themselves, and where they

naturally rely on their own agents rather than on what any casual speaker may

say.

In the

attempt started by the Theosophical Society in India, and carried on by large

numbers of the Hindûs themselves, to build up a large

Hindû College, we are trying to do the very opposite

of some of the things that are being suggested to the Government, and are

already doing some of the things they want done. We have put down the fees to

the lowest possible point; we are training the lads in the laboratory; we give

them less and less instruction in which memory only is cultivated, and in which

the reasoning faculties are thrown entirely on one side. We are teaching them

to play games; we are training strong and healthy bodies, and are endeavouring to prevent the great nervous strain involved

in study. But if this Commission Report be adopted, much of our work will be

destroyed, and the results which we are trying to bring about, and have brought

about to some extent, will be utterly wasted, will be impossible to carry on;

for the boys that we want to reach, the intelligent, the eager, those who are

longing to learn but whose parents are poor, they will be shut utterly out of

education, for unless we adopt the Government rate of fees, the Government may

close the College and not permit it to carry on its work. That is the kind of

difficulty that has to be dealt with in these educational measures. If you

would let Indians guide their own education, if you would give them all that is

best in the West, when it is suitable, but not insist that all that is good in

England is necessarily good there; if you would try to see things from their

own standpoint, if you did not insist on highly paid Englishmen as instructors,

instead of educated Indians, you would work at less expense and with more

efficiency.

But what is

there to be done, when the Government here has the last word, and knows nothing

about the conditions; and when the data on which the decisions are made are

sent from India by those who are apart from Indian sympathy, data on which the

Indians are not consulted, although it is their children whose future is in

jeopardy. What is really needed is to make education cheap, widespread,

scientific, literary and technical; to change the policy which draws the

intelligent Indians only into Government service, and to get them to take up

the other lines of work which affect the economic future of their country; to

educate them in arts and manufactures; not to leave the direction of industry

to people who are of the ruling nation, but to draft into industrial

undertakings large numbers of the educated classes - that is the kind of

education that is wanted, and the kind of education that England does not give

to India, and will not. let India give to herself.

3) Pass from

that to the third point I spoke of - the questions touching on politics,

including the social and economic conditions of India. It must have struck you, those who have studied

the past, that it is very strange that this country - which, when the East

India Company went there in the eighteenth century, was one of the richest

countries of the world - has now become a country to go a-begging to the world

for the mere food to keep its vast population from dying of starvation by

millions. The mere fact that there has been such a change in the wealth of the

country should surely make those who are responsible for its rule look more

closely into the economic conditions, should surely suggest that there is

something fundamentally wrong when you have these recurring famines. Six years

of famine, practically, India has lately passed through. It is not due to

changes of climate; these have always been there - seasons of drought, seasons

of too much rain, seasons of good weather. These are not surely the direct

result of English rule! They existed long before England came; they are likely

to exist long after we have all passed away. Why is it that these famines recur

time after time ? Why is it that such myriads of people are thus doomed to

starvation ? Now I have not a word to say as to the efforts that are made by

the English when the famine is there, save words of praise. The English

officials worked themselves half to death, when the people were dying. But that

is not the time when the work is most needed. It is prevention that we want,

rather than cure; and the nation that can only deal with famine by relief-works

and by charity is not a nation that in the eyes of the world can justify its

authority in India. There must be causes that underlie these famines. It is the

duty of the ruling nation to understand these causes, or else to allow the

wisest among the Indian population to take these questions into their own hands

and act as the Council of the English rulers. Sometimes it is said that the

famine is owing to the increase in the population. That is not true. What is

called the peace of Britain is not a blessing, if it be the cause of famine. It

is easier to the great mass of the people to have wars that kill off some of

them quickly, than to have recurring famines that starve them to death after

months of agony. The British peace is not a blessing, if it be punctuated by

famines in which millions die by starvation. Peace is not a blessing if it

kills more people than war, and that is what the peace of England is doing in

India, and it is killing them after terrible sufferings, instead of by sword

and by fire. It is the cause of these famines that we need to understand. It is

a remarkable fact that, where the Indian princes have been left uninterfered with, the famines have not been so serious.

Everywhere, where a nation lives by agriculture and has to prepare itself for a

bad season, it is usual to find out a way of dealing with the natural

difficulties suitable to its own spirit. Now that was done in India, and done

in a very simple way, although a way that is dead against the modern Political

economy. The way was a simple way as in the days of ancient Egypt. We have all

read of how when Joseph was the wise minister there, he provided for the years

of famine in the years of plenty. That one sentence expresses the Indian way of

dealing with famines. When there was plenty, large quantities of the food were

stored, and rent and taxes were taken in food these varied with the food raised

by the people and therefore they never pressed heavily on the people. When

there was much raised the rent and taxes were higher; when the harvest was bad,

the King went without his share. But in the years when he got a very large

share, he stored it in granaries. In addition to that, after the people were

fed (and the feeding of the people was the first charge), the people themselves

stored the year's corn, so that if they had a bad year they could fall back on

their own corn. In this way the peasant could make head against one bad season

and if there were more than one bad season the prince came to his aid, by

throwing his corn on the market at a price which the people could afford to

pay. Now that method of dealing with the famine problem still goes on in some

States, such as Kãshmir, because they will not permit

their grain to be exported. But the greatest pressure is continually being put

on the Mahãrãja of Kãshmir

to force him to export his rice, He has been able to hold his own so far, but

the resistance to English pressure is a terribly difficult thing for an Indian

prince, and to resist it continually is not possible. Now I know how alien to

English thought is that method of dealing with the products of a country; but

it is far better to carry that on and save the people from famine, than to

insist that the people shall sell their corn in years of plenty and starve in

years of scarcity; The people want to store their corn when they have it, to

keep it against the bad seasons, instead of having to import it from abroad in

time of famine. And yet, in this very year when famine was threatened, I saw

not long ago in a newspaper a telegram advising the recurrence of famine in one

part of India, and, in the same paper that contained that telegram, I saw a

statement that the first shiploads of Indian wheat had left Bombay. That may be

modern political economy, but it is pure idiocy. India if wisely governed may

be a paradise, but we have just read that with five fools you can turn a

paradise into a hell; and to impose English political economy on India is folly,

well-intentioned folly, but folly none the less.

Another great

cause of these famines is the way in which the land is now held. In the old

days there was a common interest in the land between princes and people. Now

the nobles, the old class of zemindars, have been

turned into landlords, and that is a very different thing from the old way of

holding land. Then you have insisted on giving to the peasant the right to sell

his land, the very last thing that he wants to do, the thing which takes away

from him the certainty of food for himself and his children. No peasant in the

old days had the right to sell his land, but only to cultivate it. If he needed

to borrow at any time, he borrowed on the crop. Now, in order to free the

people from debt, they are given the right to sell their mortgaged holdings,

and this means the throwing out of an agricultural people on the roads, making

them landless, and the holding of the land by money-lenders. That revolution in

the land system of India is one of the causes of the recurring famines, the

second perhaps of the great causes. The natural result of it is that you put

now power into the hands of the money-lender, and you take away from the

peasant the shield that always protected him.

The railway

system, too, useful as it is, has done an immense amount of harm. It has

cleared away the food; it has sent the man with money into the country

districts to buy up the produce, which he sends abroad, giving the peasant the

rupees that he cannot eat instead of the rice and corn that he can eat.

Even when I

first went to India, you could hardly see a peasant woman without silver

bangles on her arms and legs. Now large numbers of peasant women wear none;

these have been sold during these last years of famine, and to sell these is

the last sign of poverty for the Indian peasantry. It is no good giving them

money in exchange for their food. They do not know how to deal with it. They

are urged to buy English goods of Manchester manufacture, which wear out in a

few months, instead of the Indian-made articles which last for many years. You

must remember that the Indian peasant washes his clothes every day of his life,

and so they need to be of great durability.

Another

difficulty is the way in which you have destroyed the manufactures of India -

destroyed them partly by flooding the market with cheap, showy, adulterated

goods, which have attracted the ignorant people, inducing them to buy what is

largely worthless. All the finer manufactures of India are practically destroyed,

whereas the makers used to grow rich by selling these to her wealthy men and to

foreign countries. Now both the fine and coarse goods are beaten out of the

country by the cheap Manchester goods, and the dear fashionable fabrics; even

if this had been done fairly it would not be so bad, but the Indian merchants

were forced to give up their trade secrets to the agents of English industries.

You guard your trade secrets jealously from rivals, but you have forced the

Indians to give up theirs, in order that English manufacturers might have the

benefit of that knowledge. In this way old trades have been gradually killed

out, while the arts of India are very rapidly perishing. The arts of India

depended on the social condition of the country. The artist in India was not a

man who lived by competition. As far as he was concerned he did not trade at

all. He was always kept as part of the great household, of a noble; his board,

his lodging, his clothing, were all secured to him, and he worked at his

leisure, and carried out his artistic ideas without difficulty and without

struggle. All that class is being killed out in the stress of western

competition, and it is not as though something else were put in its place; the

thing itself is destroyed, the whole market is destroyed. Now the pressure is

falling on the artisan, and he is utterly unable to guard himself against it,

and is falling back into the already well-filled agricultural ranks.

These are

some of the questions that you have to consider and to understand. You have to

understand the question of Indian taxation; you have to understand the question

of taking away from India seventeen millions a year to meet Home, i.e.,

English, charges. You have to consider the expense of your Government in India, the exorbitant salaries that are paid to

English officials. You have to realize the financial side of the problem, as

well as those that I have dealt with

Friends, I

have only been able to touch the fringe of a great subject. I have hoped, by

packing together a number of these facts, to stir you into study rather than to

convince you. For if I had tried to move your feelings I would have done

little. I have preferred to point out the difficulties that have to be dealt

with, so that you may study them, so that you may investigate them, so that you

may form your own opinions upon them. I do not believe it is possible to do

everything at once, but I do think it might be possible to form a band of

English experts, who should make these questions their speciality,

and who should have weight with the Government over here which deals with

India, so that they could advise with wisdom, so that they could point out the

most useful path by which improvement could be made. To govern a great country

like India by a Parliament over here is practically

impossible. It is too clumsy an instrument for the ruling of such a people. But

if you would build up in India a great Council, composed of the wisest and most

thoughtful of her own people; if you would take the advice of her best

administrators in Indian States, her own sons; if you would place in such a

Council her greatest feudatory Chiefs; if such a Council of all that is wisest

and noblest in India were gathered round the Viceroy, who should hold his post,

not as the reward for political service here, but because he knows and

understands India, or, still better, appoint as Viceroy a Prince of the

Imperial House; if you would leave him there for a greater space of time, and

not make him work in a break-neck hurry to get something done; then there would

be a brighter hope on the Indian horizon. This can only be done by

understanding Indian feelings and not by ignoring them, by trying to sympathize

with Indian customs and not by despising them. Along these lines lies the

salvation of India and of England alike, and it is this which I recommend to your

most thoughtful consideration.

The Case for

India by Annie Besant

India

and England by Annie Besant 1914

Annie

Besant and the Indian National Congress

Theosophy and

the Great War

Welsh

Theosophists Protest against the Internment of Annie Besant 1917

Return to Annie Besant

Selection

Return to

History of the Theosophical Society

Cardiff Lodge Homepage

Cardiff Theosophical Society

206 Newport Road, Cardiff,

Wales, UK, CF24 – 1DL.

Try these links for

more

info about Theosophy

Cardiff Theosophical Society meetings

are informal

and there’s always a

cup of tea afterwards

Theosophy

Cardiff

The

Cardiff Theosophical Society Website

Theosophy

Wales

The

National Wales Theosophy Website

Theosophy Cardiff’s Instant Guide to Theosophy

Cardiff Theosophical Archive

Cardiff Blavatsky Archive

A

Theosophy Study Resource

Theosophy Cardiff’s Gallery of Great Theosophists

Dave’s Streetwise Theosophy Boards

The Theosophy Website that welcomes

absolute beginners.

If you run a Theosophy Study Group,

please

feel free to use any

material on this Website

Blavatsky Blogger

Independent Theosophy Blog

Quick Blasts of Theosophy

One liners and quick explanations

About aspects of Theosophy

The Blavatsky Blogger’s

Instant Guide To

Death & The Afterlife

Blavatsky

Calling

The

Voice of the Silence Website

Theosophy

Nirvana

Cardiff Theosophy Start-Up

A Free Intro to Theosophy

The

Blavatsky Free State

An

Independent Theosophical Republic

Links

to Free Online Theosophy

Study

Resources; Courses, Writings,

Commentaries,

Forums, Blogs

Feelgood

Theosophy

Visit the Feelgood Lodge

The main criteria

for the inclusion of

links on this site is

that they have some

relationship (however

tenuous) to Theosophy

and are lightweight,

amusing or entertaining.

Topics include

Quantum Theory and Socks,

Dick

Dastardly and Legendary Blues Singers.

Theosophy

The

New Rock ‘n Roll

An

entertaining introduction to Theosophy

Nothing answers questions

like Theosophy can!

The Key to Theosophy

Wales!

Wales! Theosophy Wales

The

All Wales Guide To

Getting

Started in Theosophy

For

everyone everywhere, not just in Wales

Brief Theosophical Glossary

The Akashic Records

It’s all “water

under the bridge” but everything you do

makes an imprint on

the Space-Time Continuum.

Theosophy and Reincarnation

A selection of

articles on Reincarnation

by Theosophical

writers

Provided in

response to the large number

of enquiries we

receive on this subject

Theosophical Glossary

prepared by W Q Judge

The

South of Heaven Guide to

Theosophy

and Devachan

The South of Heaven Guide to

Theosophy and Dreams

The South of Heaven Guide to

Theosophy and Angels

Theosophy

Aardvark

No

Aardvarks were harmed in the

preparation of

this Website

Theosophy Avalon

The Theosophy Wales

King Arthur Pages

The Tooting Broadway

Underground Theosophy Website

The Spiritual Home of Urban Theosophy

The Mornington Crescent

Underground Theosophy Website

The Earth Base for Evolutionary Theosophy

Theosophy

Birmingham

The

Birmingham Annie Besant Lodge

_________________________

The Theosophy Cardiff

Glastonbury

Pages

Chalice Well, Glastonbury.

The Theosophy Cardiff Guide to

Chalice Well, Glastonbury,

Somerset, England

The Theosophy Cardiff Guide to

Glastonbury Abbey

Theosophy Cardiff’s

Glastonbury Abbey Chronology

The Theosophy Cardiff Guide to

Glastonbury Tor

The Labyrinth

The Terraced Maze of Glastonbury Tor

Glastonbury and

Joseph of Arimathea

The Grave of King Arthur & Guinevere

At Glastonbury Abbey

Views of Glastonbury High Street

The Theosophy Cardiff Guide to

Glastonbury Bookshops

_____________________

Tekels Park

Camberley Surrey England GU15 2LF

Tekels Park to be Sold to a Developer

Concerns are raised about the fate of the wildlife as

The Spiritual Retreat, Tekels Park in Camberley,

Surrey, England is to be sold to a developer

Future

of Tekels Park Badgers in Doubt

Magnificent

Tekels Park to be Sold to a Developer

____________________

H P Blavatsky’s Heavy Duty

Theosophical Glossary

Published 1892

A

B

C

D

EFG

H

IJ

KL

M

N

OP

QR

S

T

UV

WXYZ

Complete Theosophical Glossary in Plain Text Format

1.22MB

___________________________

Classic Introductory

Theosophy Text

A Text Book of Theosophy By C W Leadbeater

What Theosophy Is From the Absolute to Man

The Formation of a Solar System The Evolution of Life

The Constitution of Man After Death Reincarnation

The Purpose of Life The Planetary Chains

The Result of Theosophical Study

_____________________

The Occult World

By Alfred Percy Sinnett

Preface to the American Edition Introduction

Occultism and its Adepts The Theosophical Society

First Occult Experiences Teachings of Occult Philosophy

Later Occult Phenomena Appendix

Try these if you are looking

for a

local

Theosophy Group or Centre

UK Listing of Theosophical Groups

Worldwide Directory of

Theosophical Links

International Directory of

Theosophical Societies

WALES

Pages About Wales

General pages

about Wales, Welsh History

and The History of

Theosophy in Wales

Wales is a

Principality within the United Kingdom

and has an eastern

border with England.

The land area is

just over 8,000 square miles.

Snowdon in North Wales is

the highest mountain at 3,650 feet.

The coastline is almost

750 miles long.

The population of Wales as at the 2001 census

is 2,946,200.